Jüri Talvet

HOMAGE TO ALBERT CAMUS, IN MARCH 2020 Would you mind going right now to the grocery store:stock up on toilet paper, many rolls, and macaroni noodles,butter, jam, and beets, turnips, as well as carrots,run, be quick, hurry - before the market is cleaned out! I run, I buy, I hoard. No reason, but I run,I buy, I hoard. For the first time in the history of Estonia,a state of emergency has been declared. Scientists’s voices are stopped,no one knows the cause. But people keep dying, the infection spreads! States shut offices, close borders. Even corporate sharks are filled with fear and czars are trembling in their kremlins.A new grand migration of peoples is impending, the start of the new long Middle Ages ‒ a sign of punishment from heaven! Death can drag anyone to its dance. Suddenly tame lifeseems to rebel against its lords - those who have caredonly for themselves in the tiny mote of life,extracting from it their wealth and treasures! Run, be quick, hurry - before the market is cleaned out!I run, I buy, I hoard. No apparent reason, yet it seemsthe right time has come to read a small bookbefore it disappears from all the library shelves of the world! Its author did not foresee his own death at only 47,yet, better than the Bible or the Qur’an he divinedwhat a human soul could do in misery, such as a war (then just ended,with no one guilt-free). Let them read, then, all who can read, and let others read to those who cannot! Let hands be washed, whole bodies,let souls be swept clean of dirt, let all be awakenedbefore it's too late, before death invites all to dance!Let garlic be eaten at all costs, even by those in perfect health! Let it be read in solitude and read to others ‒ the book whose titlevaries by language, but means always the sameand is as short as "death," a single syllable, sometimes two,a flash and all is lost ‒ a word that gathers, in any one life unites fear, death, and hope of love:

Peste! Plague! ‒ let corporate sharks and tsars in kremlins tremble!

Чума, प्लेग, 瘟疫! ‒ let garlic be eaten, let souls be swept clean of dirt!

Mēras, maras, katk! ‒ it unites fear and death and hope!

(Translation from the Estonian by the author and H. L. Hix)

***

LETTER 1

Cher Michel de

Montaigne,

I write to you from Rhodes, the Greek island which since you left this world has had a complicated and bizarre history. For several centuries it was dominated by Turks, and Italians ruled here in the first half of the 20th century, but after WWII it became Greek again. From the window of my room at Rhodes’ international writers’ center I can see a fragment of the blue Mediterranean, with grayish Turkish mountains on the opposite shore. Directly in front of my window, a palm-tree, though half-withered, stands proudly erect, in defiant resistance to the winds. A group of crows tries to land on its crest, but the wind pushes them away, until finally they give up their enterprise and leave.

I write you because, especially in recent years, I have come to value you as a European thinker whose ideas often confirm my own meditations. Ideas similar to yours emerge also from the work of a number of brilliant writers of your time, which now we call the Renaissance. I have in mind Erasmus, Thomas More, and Rabelais, your predecessors, as well as the English poet and playwright William Shakespeare, who was inspired by your Essays shortly after you had passed away. Shakespeare’s plays and poems are still staged and read all over the world at the start of the 21st century. Similarly, posterity has treasured, as I am sure you would have, the hefty book entitled Don Quixote (Don Quijote, in Spanish), by the Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes, who died in 1616, the same year as Shakespeare. In the work of a few other talented and philosophically-minded Spanish writers of the 17th century (Francisco de Quevedo, Tirso de Molina, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Baltasar Gracián, some of whose work I have translated into my native Estonian), and that of a small number of Western writers since, you would recognize echoes of the same spiritual and mental notes that sounded in your own essays.

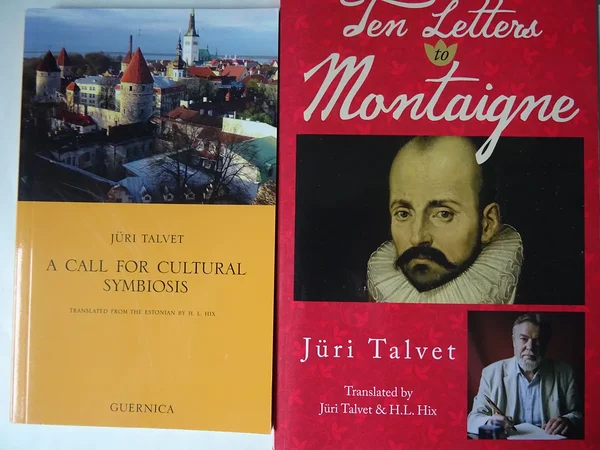

[See further Ten Letters to Montaigne. "Self" and "Other". Trans. J. Talvet and H. L. HIx. Toronto: Guernica, 2019]

I was born after the last great world bloodshed in a small European country whose autochthonous population numbers barely a million. For brevity's sake, let's call it U. I have chosen the letter "U" because I noticed only recently that the words for some essential notions in my native language are said with the sound and written with the letter "U" in them - in the stressed syllable. These include the words for "death", "fire", "earth", "ashes", "God", "sadness", "evil", "sleep", "snow", "sex", "melancholy", "madness", "spell", "pride", "story", "poetry", "faith and religion" (there is a single word for both in my language), etc. (Only now I notice that in English none of them has a "U".)

[See further: A Call for Cultural Symbiosis. Meditations from U. Trans. H. L. Hix. Toronto: Guernica, 2005]

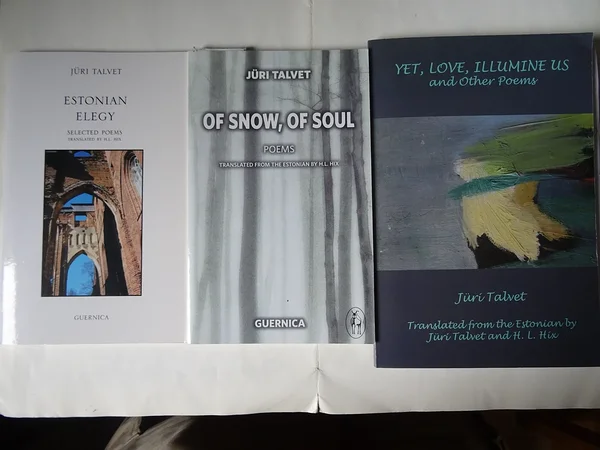

from ESTONIAN ELEGY. SELECTED POEMS

(Translated by H. L. Hix. Toronto-Buffalo-Chicago-Lancaster: Guernica, 2008)

CAROUSEL AND GIOCONDA

The carousel had horses

and we ourselves pushed it

around under the pavilion.

(Was Carousel the name of your childhood street

or simply of your childhood?)

The carousel, as you now read,

was not only riding horses:

panoplied knights

threw each other with bleeding spears

under the smirking glance of Gioconda.

(Under the sun that with the same weariness

observed them before us.)

Spears pierced childhood.

Now you are yourself a spearman on a carousel.

A motor moves the horses

and gives orders to your hand.

(Gioconda the avatar

laughs her mad laughter.)

BRIDGES, ROADS

Cars rush across the bridge

golden glint of glass at one point

the only more certain sign of existence

a woman hurrying alone on the sidewalk

smiles to herself

bears on her face the same sign

before the discontent of arrival

bridges and roads splice

and sever

what secret microscope could enlighten the ants' brains

their terrifying purposefulness

under the crow's cacophonous song?

ON LOSING A PASSPORT

The passport lost — long live liberty!

A frown fell from your face,

the stamp's stern shield suddenly gave way,

and having shrugged from your shoulders twenty years

and the border guard's careful watch,

you plunged into liberty. Liberty!

No address drew you back,

no signature, no Ariadnian thread of the future,

not even the myth with the help of which

you prudently tried to multiply yourself.

Rain and sleet chip at you,

foreign hands crush. Your form

fragments under trampling feet.

(Soon you yourself will feel the weight of history's feet.)

Liberty! Into the airspace where you were

a fresh snowflake floats, and briefly pauses.

SURPRISES OF CLIMATE

Waiting for reward, we decay into age.

It would have been better to pasture sheep,

to shelter under a tree while it rains

and listen to the fulminations of God,

himself a lamb, in his just peace.

Or to cut wood in the forest, until

gradually the working body fits

the rhythm of the falling tree, like an ax.

At least to cut a wedge into loneliness.

No one writes to the colonel.

The charlatan stirs on the stage his eyes

and the dust. He is praised to the heavens,

but at night every last speck

reassumes its spot and its stillness.

So when suddenly a warmer wind

from the future starts blowing,

we are perplexed, having forgotten

how to hoist our shirts as sails.

GODSPEED

We depart. Farewell and abrazos

remain hovering like a frightened handkerchief in the wind.

Lightness, smell of seaweed over a blue abyss.

Something warm, like a sleeping child in you,

takes root even as it painfully ceases.

We have not yet turned our backs on each other,

but already I know I will step at once

into my loneliness. We stepped

through each other, our hearts beat in consonance

when we stood face to face. We reach back

from our rapidly retreating autumns,

grasping for the fire of childhood, fearlessly.

Then with rejoicing ring telephones

and doorbells, tapping on shoulders

like soft Northern snow,

toasts flow with fluent praise: welcome!

Greetings on your return to the living,

you little one lost, on the cemetery paths.

SPRING AND POWDER

It glides, the day of our death,

before and behind us, stubborn as stone,

still pure, waiting for love.

People move today

through soft spring mist

after obsessive cold winds

need no answer

to smiles

since the smiles start

from within

Time as a mist rests

on walkers' shoulders

and no one any more

wants to go farther

A step ahead waits work:

Warps, webs, shrouds must be readied

to cover all dark,

wild, to try to forget it

and every forgetting carves

a furrow into the forehead

Already all is covered

Powder levels the furrows

Centuries prepared this moment

Forgotten are bones and snow

All is readied

Who now will give us love?

FULFILMENT

You creep quite close under my chin,

nest there — nowhere else is it warmer —

there is your Milky Way.

You have shared yourself,

have given birth, been torn in labor.

Do you remember those small,

barely discernible paths

that stretch farther than your own?

You have remained. I do not think

of those blood-colored flowers you lavish on me,

never refusing, from the garden of your nights and days.

Of course you are always open to error — free —,

since around us souls hover in the wind of abjection.

The gold of beginnings is released inside you

and fulfilled under my chin, on your Milky Way.

(The poem "Fulfilment" is from: On the Way Home. An Anthology of Contemporary Estonian Poetry. Edited by H. L. Hix, translated by J. Talvet & H. L. Hix. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2006)

A DREAM OF GERMANY, 1988

With thanks for inspiration to Nicaraguan poet Joaquín Pasos

Germany, 43 years after history's most miserable shoemaker.

Mr. Grass lives on the other side of a wall

built to be wholly free from the cat-and-mouse complex.

But now roiling winds threaten from the East

where ordnung is not in ordnung.

As a counterweight this side vehemently follows

the theorem of a full stomach's simple consequences:

the traveller can smell the rich pigshit smell from the fields

and German bellies, gladly gurgling, digest

bockwursts and würstchens, bettered by beer.

What matters memory — rat-colored barracks —

and what matters the pensmith, even in dreams seduced by a she-rat?

After all, for whom did the fire-eyed man

with the streaming beard write his hinweises, if not for us!

No point in arguing: here is sozialismus funktioniert.

The strong breasts of young German women (which in summer

they do not try to conceal) proclaim a hopeful future for the German race.

Old women never tire of planting red roses between rat-colored houses.

The freckled boy, who for ten minutes

persistently and fruitlessly — on tiptoe, his tongue sticking out —

tries to cajole a stamp from the stamp-machine,

is Hegel or Leibniz, not — rather Schopenhauer (luckily!).

Bachs and Händels nod peaceably on their pedestals in town squares.

True, the young Luther (in Weimar, in Cranach's picture)

still has a heretic's secretive air, and no one forbids a modest dream joke:

one evening at twilight — still in Weimar —

the old gentleman Goethe, tired of his timeless importance,

sneaks to his Goethe-haus a few streets away,

and with an unmistakable finger movement — as at the same hour

on the same night thousands of East Germans, driven

by their other, insatiable hunger — conjures into the rectangular miracle box

the magic smile of the young woman from westdeutsche TV.

SUPPOSE DUST BELONGED ONLY TO THE BEYOND

The sky stays blue

this Estonian spring.

(Anticipation or omen?)

Words free the horizon,

and suddenly we are better

than we were. This

is something new: as if

the unfading coffins

that float on the wind

of your fancy would refuse

to serve evil. Or good, either.

But dust — any dust —

still holds more sorrow

than a living body. Thus the strange

imbalance here, in the living, which

with portent and promise

imitates the other, the real,

the especially blue sky

of spring in Estonia.

May 1988

BLASPHEMOUS

Liberty is a leviathan

you will never catch.

Liberty is a leviathan

the padlock of power itself

cannot confine.

Hoisted atop the state tower,

fluttering from the state tower

is liberty’s tale.

YESTERDAY I WAS AN ANDALUSIAN DOG

Death, release me

from your terrible, deep teeth!

I am your other: a flying limousine

that flashes to you

its fulgurating signal color,

a dog that has unlearned barking,

made to speak, a toy dog wagging its tail.

(Yesterday I was an Andalusian dog.)

The secret is in mass. All secrets,

all slynesses meet in mass.

A suspension bridge between mouths,

I feel, I channel pure and impure words.

My floor is the past, my ceiling the future.

I am a mute cartwheel. I whirl

the present around my finger.

I am the moss-covered belly

of the aqueduct on its eight sturdy thighs,

water draining from one time to another.

THE CASE OF MARC

Was your crime old age,

your clumsy, slow tongue,

in the soft bed of your young wife?

As sovereign you lacked

neither training nor nobility.

O Celtic love,

between invisible golden hair

and the daily brightness of a white wrist,

a chasm of difference!

Sweet Marc,

you were not guilty.

The unhappy hour raised you

into the vicious contour,

and forced from it

the evergreen God himself!

ESTONIAN ELEGY

Shortly after midnight on 28 September 1994, in an area of the Baltic Sea sailors call "the ship cemetery," the passenger ferry Estonia, en route from the Estonian capital Tallinn to the Swedish capital Stockholm, sank, taking with it to the seafloor more than 900 human lives. No other peacetime shipwreck on the Baltic has claimed so many victims. Technical failure and human error are among the possible causes of the wreck, as is a criminal act. The only certain conclusion of the investigating commission is that the huge ship was brought down by water.

No, it cannot be true.

Cramps of disbelief constricted throats that morning.

Legs turned to lead, as if earth were dragging us to its roots,

the way water tore them, naked children,

suddenly from their dreams to her iron-cold breasts.

No, it cannot be true.

Liberty should have meant warmth at last, and joy.

As always, among the first, Estonia pushed forward proudly.

The tether tied to us from twilit past times

could be forgotten finally, and the dark Middle Ages

with their foolish taboos could withdraw.

Had there not been enough bowing already

to German lords, scions of Vikings, Russian wags?

Enough hauling of stumps and stones at the marsh's edge?

And now that the people had power in its hands,

why could not the feast of the body's solace last forever?

(In this land the breath of prophets put pressure

on both ears. Hegel, Marx, Lenin, Bakhtin…

Who from the left hand, who from the right, depends

on which side of the map you adopt. Poor little Jew Yuri Lotman,

on the sad, fragile middle way, had no hope of becoming a prophet,

his eyes no longer open to the sky, here at the cemetery in Tartu,

Europe's dump, last year on a biting autumn day, homeless,

speechless, taken now for Russian, now for Latvian,

his only eulogy the violin's nightingale song

by the nourishing river that indifferently, coolly flows past.)

No, it cannot be true.

What stupid sophistry about God, sin, the duty of fasting!

Where was Christ when the Knights of the Cross killed

the children of Mary's Land and raped women and girls,

when, barely having roofed the first rooms of our own,

we found ourselves back on the snowy Siberian plains gnawing on permafrost,

at the waste land's rocky dump, there from where they say we came.

No, it cannot be true.

For thousands of years already we have been Europeans:

early tillers, at a time when others, the stronger,

consumed their neighbors, like an insatiable swarm of grasshoppers

discovered and plundered new continents,

driven by hunger, by the darksweet womb of a foreign woman.

Then a precipice, bitterness, anyway the cool grin of death.

Is small size proof of nobility? Have not we also desired

a midday under our mournful skies?

The king of Estonians rising from the field of Ümera,

his sword, bright with the blood of the foreign exploiters

pointed exultantly to the sun!

The ship's lights went out suddenly;

in the water's womb, amid seaweed, shoals of silent fish,

a school of children slept, dreaming

of a clear, bright summer morning.

No, it cannot be true.

We have waded in the mud of history,

calling for help from the bastards of our lords.

But who would recognize the puny name of Sittow

in the endless halls of Europe's castles,

in the numberless flock of Low Country painters?

Who would notice Schmidt's sweat and soul

in the lens, piercing into space, that illuminates regardless,

or Martens, among the faithful Russian civil servants,

in the rear of the regiment, without a necktie?

Then, Peterson, the Estonian Keats taken too young to the grave,

and the father of our song, Kreutzwald, who conducted the hero

of Mary's Land to Tartarus, as Vergil did Dante, to find love there.

(By that time the German Faust already sat comfortably

on the knees of the Virgin in heaven — late, always late!)

Or the singer of sunrise, Koidula, whose streaming

ravenblack hair proved the descent of Estonians

from the Peruvian arch-Inca, just like

the brush of Viiralt, made of Berber women's hair.

Who would learn to pronounce their names, or the even less

sonorous, clumsily compound Tammsaare?

Who would care about his earth-colored proofs

in a language the same as the tongue of Basques,

the nahuatl of Indians, the nonsense sounds of Celts.

No, it cannot be true.

Now Estonia sank again to a common grave,

so suddenly there was no time to divine

who in the mist of times had been master and who slave,

who until the death hour had fornicated in the bed of pleasure

and who had loved the homeland.

Oh, rage of the dance of death! Just as the clothes

are torn to flesh and flesh to bones

of the ants who always made provision, so of those

who let today's wind blow through their thin bodies!

Oh, alphabetic death, whose laughter does not mark

the darkness or brightness of our intellectual signs!

All words bore the zero-sign when

an Estonian stretched his hand to a drowning Russian,

when a dry Swede from his scraggy breast

withdrew warmth to tender it to a freezing Estonian.

Not in this century had the ironwet foot

so trampled, until blood flowed,

the mighty frame of the Scandinavian lion.

No, it cannot be true.

How could that other wave still comfort

that had reached from an even darker night,

evil behind our backs, threatening,

that Estonians in the joyful shouts of song festivals

wearily, dreamily, vainly invoke and erase?

I am not interested in your cemeteries, nor in your proofs

that in your graveyards is hidden another, bigger state.

I am interested only in life, the capacity

of our kaleidoscopic time to give a unique pattern to colors.

Just an ethereal turn, just a fourth of a degree

of skillful movement learned from the Greek artists,

opens the safe, blessed niche!

No, it cannot be true.

For thousands of years already we have been Europeans.

Thousands of years before Marx and Friedman

we knew that Penelope's heart

would not stay cold to the Tyrian purple

and that Odysseus, cavorting with naiads,

really hopes the journey home will never end,

and that the poor orphan Telemachus is Oedipus,

persistently pestering his parents

who build their bed ever wider,

as the East-Slavonic sensible germ

pestered the French prime minister, who

in the early 1990s shocked his colleagues

by firing a bullet into his head.

Again you come out with your myths,

but we simply have no time for them. Why

should the two of us, Señor González and Herr Kohl,

worry about the crumbling ozone over our heads

or have nightmares of drowning Estonia or sinking Europe

if our heads and stomachs ache each weekend

for worry over how our beloved countrymen

in their beloved cars can get to beaches to inhale more oxygen,

how it is possible that today Real could be beaten

by Bavaria so badly, or vice versa,

and how the fluctuation of sausage prices has been influenced

by the air wall, the spirit of Marx that, as before,

hovers sneering between Unter den Linden

and Tierpark — despite our mighty hammers,

despite our warm embraces!

No, it cannot be true.

For thousands of years already we have been Europeans.

At our rebirth, as midwife,

Plato nervously bustled. From him we learned

that the idea of love is more important than love itself;

he illuminated the rose that blossomed in Eco's mind

and guided Lotmans' forceps,

which from the gelatinous well

drew to daylight struggling signs of life.

Had Plato ever loved?

We do not know, despite

his protestations that love

could not nestle in the beloved,

but only in the lover himself.

Well, there are the lovers themselves:

amid the rubbish drifting in the Singel Canal

in Amsterdam

they leave their sad saleable ingredient —

whether from green, black,

or white skulls, from wrinkled

or smooth brains.

(Look at muddy Rembrandt, ecstatic

spermatic Van Gogh

painting despair that floats

amid the chunks of flesh.)

How would you like to go home, to yourself,

to the green morning mist of Estonia, to the heart's depth and breadth,

there where Europe shakes from herself

the omniscient sludge of evenings

and is a child again!

But you know nothing of yourself —

until the moment when from behind a wall

rising to the heavens (built of unnumbered cities,

mountains, rivers, deep

triangular wells, women's breasts,

oblivions, graveyards with skeletons

and crosses, silver hair, crowns of veins,

and memories) breaks a longing,

a voice that does not begin only in myself.

(Many prophets have died without living that longing,

or lived without dying from it.

Look, Plato, that is why love in yourself alone is insufficient,

and even less the idea of love.

But the Green Knight tests the living

at least three times: are you faithful!

Be steadfast: one from whose scalp

the golden curl of vanity has not

by the third time fallen

will not raise his head!)

All this could be called a sign, a mist,

a dream, something that cannot be true,

that vanishes at once,

— as that night wise computer craniums

blinked out into the opaque mist of algae —

had you and I not been there

at that moment when God did not yet know

whom to name Europe, whom to name Estonia,

whom rose;

what to name us, who (having been born into the universe

unfadingly from whatever earth, water,

whatever odor, seed, fire,

whatever distances)

are true. Just so, we ask

of ourselves, we who receive ourselves,

tenderness (more than a name), love (more

than blood), light (more than bones).

Just so, and only so, are we true.

October 1994

FROM SANTIAGO’S ROAD

III

(A dream of Europe)

In the end, our task is to multiply the blue sky,

the peaceful dream of sunrise,

to take the grey rag from the eyes,

to be a lake that washes its eyes, a forest that readies

its green bed, not to fear being an ocean that expands,

a well that explains.

The republic of course only imitates liberty:

every state is a mark of the stamp, every president

a cartoon parrot.

In every Republic one learns anew to escape

the clever corridors the great architect designed,

while into the expanding cracks power sucks

parrots and lions,

chiggers and men.

Above all, fear the cruel, mad sectarian.

Better be a pagan barbar, till the point of the toe.

Better a mad Roman, until Christ.

In everything the fear of love is guilty.

Too capriciously screamed the apple, but justly

the sink moaned under the burden of nightly ablutions.

We do not sow culture here,

it grows by itself and breeds us.

While presidential beaks clap shut

and the West wails in labor, pregnant with joys

it cannot deliver,

invisibly Europe sends out shoots of balance

always green near the heart.

OSSIAN’S SONGS

2

You have read the Book of Kells.

Ringabella rang in your ears like a beautiful ring.

Already the days could be paper-clipped together:

good and bad, praises and dispraises in pairs.

Sheets of a timeless book, around them only thin air.

Errant letters on the margin - Today under my pen

in the bright sun the parchment shone gold -

inspired even more.

The day’s gifts of love seemed to have

the same weight. They showed the same

confident coil of logic. Aba bdb ded efe

fgf etc. - like the metric of Dante’s verse

that remembers the past and is always full of the new.

But it is pointless for me to intrude into your day.

In the same way that night shuts your swinging door,

carelessly pushing from the sheet your careful pen,

I, Ossian, by the bay of Ringabella

on a moonlit rock await the blind lightning of death

that must strike me, the red lance of love

that pierces me from behind.

MY LIFE WITH NOISE

Yes, it is said: "They have no wisdom, no depth."

(As if wisdom conferred the privilege

of one's own bite of daily bread.)

They have only noise, mouths

that blink together like eyes, polished teeth

that together throw thunderbolts.

We, the deep, close our thought

into that safe sarcophagus, silence.

Their shrill laughter and noisy hammering voices

break through walls, penetrate

every barely living bone.

(Every insect, every tree smells them.)

We work, so love will follow.

They love without work, joyfully.

We try to dampen them with depth, make them good.

We are good, they answer, from the very darkness of the well.

The autumn wind indifferently washes both our faces.

Even the death hour does not tell

who owed whom words of gratitude and praise.

BELIEVE WHAT SIGNS YOU LIKE

No matter that your ancestors

spoke another tongue,

a tongue that now no one knows.

A shield wrought with words

defends only during peacetime.

In wartime, the time of love,

you spoke to me in the oldest tongue,

darker than your dark hair,

deeper than the stammering words

of your ancestors, more alive

than the blood of your red lips,

defying with your tongue

the dividing lines of the word,

fearlessly smuggling onto my tongue

a taste greener than grass,

more like the sea

than the sea itself.

21st BALTIC ELEGY

To Ivar Ivask, cherished friend, who was born 17 December 1927 in Riga, grew up and studied in Riga, Rõngu, and Marburg, where he met his faithful lifelong partner the Latvian poetess Astrid Hartmanis (whose name means "asters" in Estonian), was professor of literature in the USA and for 24 years Editor of Books Abroad/World Literature Today at the University of Oklahoma, founded the international Neustadt Literary Prize and the Puterbaugh series of symposia celebrating modern literature in Spanish and French, brought Baltic literatures for the first time into world evaluation, published eight books of poetry in Estonian, drew pictures and travelled tirelessly, wrote in English, in Ballycotton, Ireland, the major part of his Baltic Elegies, a cycle of poems (now translated into numerous languages) about the history, destiny, and aspirations to freedom of the Baltic countries, and on 23 September 1992, having recently moved from Oklahoma to Fountainstown, Ireland, left the living world.

Oklahoma fell silent, the Baltic froze.

From Kafka's offices came glassy gentlemen.

The narrowing lappets of your Irish coat closed around you.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

Now you are yourself the well that draws up pails of clarity,

expands, timidly draws back, spreads out it shoots,

nourishes sensitive branches, beams of light.

Then absorbing emptiness. Then the shattered veranda.

The dazzling light of the shroud, the only voice

your aunt's clock ticking into the present, the bloodstone ring

of your mother who died young, the unnamed island of your father.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

What islands had you not visited?

Islands of poetry in the nervous swirls of Aeolus,

with dangerously heavy word plains behind.

The island of asters light in the lap of the warm Mediterranean.

But on Naxos you, archer, were afraid of your animal,

darkness. The sun enticed you, Icarus,

and banished you finally from the rough forests of Finland.

You built your pyramids of air rather than blood.

Did you fear blood? Of course you did

(like that other poet of pain and blood

whose trembling heart in 1936 under olive trees

was carried to its death by gloved hands).

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

Your element was air, you, hijo del aire,

the fine lines of your pencil started from the annual ring,

then disappeared on the white sheet

into imagination's crown, like your home begun on the light veranda,

carved by your father, the dark chimneyless hut of Rõngu,

from warm chestnuts on the road to school in Riga, the reticent softness

of your mother's brown eyes, of woman's fingers, of Latvian asters,

became unnamed love, transparency risen from the sea,

Baltic amber through which only the beautiful face

of the world, God's island, can be seen.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

There was no time to see you again, to visit

was impossible, but you were already in me,

you, double archer, brother beyond the senseless barbed wire between us.

When my father died, you said now, only now

you have yourself become father

(having left, in some sense, once again).

But truly your children were poems,

drawings, paper children that now must confirm

their father after the manner of poetry,

as holders of blood, bone, and light

before the face of the highest Father, but you

brush off the dust of time, the coat of impatience

and naked, pure, bold, recede already

into our common earth.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

You waited until the cockcrow of liberty

that you, too, had grown in your heart's homeland.

But in vain you tried to return to Liberty Square,

when strangers took your poems written in a language

strange to them, and Tallinn tilted its towers toward you.

By then you had already returned, been crowned with a wreath,

according to good song festival custom, been lifted awhile

onto shoulders when you, Icarus of free flight,

archer unknowingly sending your arrows,

stealthily slipped from the fingers.

Too indefinable suddenly was your amber honey,

Mediterranean salt, Irish coat tasted by knobby mannequins

that on the borders eagerly lifted posts out of stones

only to drive them home again, while you, boundlessly foreign to boundaries,

planted aster and tulip

and forgave, as you always had forgiven.

Your fate was to bewitch amalgams

from a flying island unattainable to Munch's fibrous palpi.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

When they expected from you a sharp biting whistle

you answered with homely birch whisks

that healed scars. When they expected piles of wise paper

you sent them off generously, distributed kindly,

to make that much freer your heart's departure.

You hastened from one continent to another, hurried

from one island to another, formed a bridge to homelands

waiting in the distant future.

The burden grew greater. When you reached the bottom,

the focus of your sharp glance grew double.

(The double Vienna, the two-branched day.)

The single-story homes were unprepared for your visits.

Finally you grew tired, and without warning

simply stepped aside, went to rest in the Irish fog.

You blue-eyed childlike festinator to the future, Ivar.

Asters burning tirelessly accompanied you along the road.

Invisibly, asters will continue to cast light on your amber grave.

[1] Yuri Lotman (1922-1993), a world-famous cultural semiotician, was Professor of Russian Literature and Semiotics at Tartu University. According to his will, at his funeral (attended by Estonian President Lennart Meri) no speeches were given. Instead, a Jewish violinist played a song based on a poem by a major Estonian poet of the "Awakening" period, Lydia Koidula (1843-1886), who was also called "The Nightingale of the Emajõgi." The Emajõgi — the Mother River — has for Estonians symbolic importance as the nurturer of Estonian national culture.

[2] Maarjamaa (Mary's Land) is the traditional poetic name of Estonia.

[3] The Finno-Ugric tribes, from whom Estonians, like Finns, Hungarians, and many other smaller peoples, are descended, may have come from western Siberia thousands of years ago.

[4] Now that Estonia has regained independence, and now that Finland and Sweden have joined the European Union, discussion of "becoming European" is more intense than ever.

[5] Among those claiming that the Estonians were Europe's first tiller tribe is Estonian President Lennart Meri, who has published several books on the origins of Finno-Ugric peoples.

[6] In the battle of Ümera, in 1210, Estonians (who along with Lithuanians were Europe's last pagan tribes) defeated the German Knights of the Cross, but not long after that battle both German dominion and Christianity were imposed on Estonia.

[7] Sittow, Schmidt, and Martens are characters in the novels of Jaan Kross (b. 1920), a major Estonian writer who has more than once been proposed as a candidate for a Nobel Prize. Mainly he has written historical novels, trying to evoke some brighter moments in Estonia's spiritual history since the late Middle Ages.

Michael Sittow (Four Monologues Concerning St. George, 1970) is a Tallinn-born painter (1469-1525) who was in the service of Spain's Catholic Rulers and also painted a portrait of England's Henry VII. Kross sometimes makes fun of his name, "sitt" being the Estonian equivalent of the English "shit."

The Estonian astronomer Bernhard Schmidt (Head Wind Ship, 1987), who lived in the early twentieth century, is recognized for having developed a new type of telescope.

Friedrich von Martens (1845-1909) was a diplomat and lawyer in Tsarist Russia, of Estonian origin. In The Departure of Professor Martens, 1984, Kross connects him with the creation of international law.

[8] Kristian Jaak Peterson (1801-1822) was the first Estonian-born poet, and a student at Tartu University. His poems praised the beauty of the Estonian language.

[9] Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803-1882) is the author of the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg (The Son of Kalev, 1861), which was inspired by the Finnish poet Lönnrot's Kalevala.

[10] An ironic allusion to the sometimes exaggerated search for "pure Estonianness." During their history, Estonians have become mixed with many nations. Lydia Koidula adapted from German a story The Last Inca of Peru, where the battle of Las Casas for the rights of Native Americans is mentioned. Eduard Viiralt (1898-1954, Paris) is perhaps the most original of Estonian artists. His mainly graphic works incorporate elements of Expressionism, Naturalism, and "Magic Realism." Among his best-known works are nudes of Berber women, which he made in 1938-39 in North Africa.

[11] Anton Hansen Tammsaare (1878-1940) is sometimes considered Estonia's greatest novelist. His major work is a novel cycle Truth and Justice (1926-1933), in which he attempts to depict symbolically the struggle and development of Estonians from the end of the 19th century to the period of independence.

[12] Hundreds of thousands of Estonians gather each summer for week-long outdoor song festivals featuring traditional Estonian folk songs.

(trans. H. L. Hix; Toronto: Guernica, 2010)

WHERE MEMORY DWELLS

Paper is bounded air

that absorbs words —

no less fragile or fugitive

than slate or screen

with electronic nerves.

The wind rattled a window.

Whose hand softly stroked

the hair of a sleeping child?

What stirring branches

what mist on whose lips

what beckoning from grass

composed the song of songs?

Behind a wall of slate

of paper of artificial nerves

(do you dare?) memory dwells

(have you already started

planning escape?)

preserves forgotten things forgives you

for your hesitation now

A DREAM COULD HAVE CONTINUED SAY LIKE THIS

You yourself are away, but the space

you’ve vacated does not withdraw

completely. A small voice rises

from beside the wardrobe, from ten years

earlier: this shirt has daddy’s smell.

Then, furious, now truly

from across the ocean, already nearly

a man: why don’t you call, father?

The floors bear the weight

of our mingled footsteps,

the window panes gather

morning gold into one place

for the eyes. Here in California

sleep frees you for loneliness,

floating lightly, dreamily.

There at home the sun shines early

into the room in which you can emerge only bound,

slower, more tired, more alive.

HOW THEY ARE

They tear us tirelessly head to toe.

They thrust long thick needles into our hearts.

Their invisible fingers pry open our eyelids at night.

Why do you always worry, mother?

What a worrier you are.

They are torn from us,

made alien,

by green signals, voices

we cannot hear.

But you keep waiting for them,

in the late fall observing marsh in frost,

bearing in yourself one more of them, half your life

past.

(Now it’s here: a new, small, beautiful life,

in a mad rush to liberty.)

They push us out of their way, laughing, loving.

They were children, who now suddenly are adults —

before we ourselves

have grown up.

REALITY

Why lift the corner of a doormat why hope

to find a forgotten key? Alberto Caeiro

was right: symbols, signs do not exist

fourfold meanings “hidden truths” do not exist

Everything is just what it is: no one

can reverse your mother’s departure

spells do not help nor do your attempts to cry

gain God’s approval Similarly you cannot prevent

the joy your little daughter takes in you

from being the same your mother felt as a child

in the autumn-cold pasture of Mõisaküla

when her young dark-eyed and black-

mustached father arrived in his wagon

to take her home for a weekend

What did STC do in Göttingen on the Veenderstrasse

in a nice bourgeois house two hundred years ago?

Did he despair because of the failure of the childish

story of Christabel or because of the birth four

or five years later of EAP whom hallucinations

and spirits would call to the grave prematurely?

Another more likely version says it was in

Göttingen on the Veenderstrasse in a bourgeois bed

after snuffing a candle and saying his bedtime

prayers when STC moved his body into just

the position that brought to mind the brown eyes

of a lovely burgher maid of Hessen that

he suddenly began to hear Hamlet’s heartbeat

NOTE TO ÁLVARO DE CAMPOS

What is reality? A heap of bones. Therefore

we build, only therefore do we imagine

mixtures of ashes and dawn — pronouncing walls

for a house where perhaps a little girl will live.

ENTERING SUMMER

Summer rain’s arrival made bus windows

shed abundant tears.

Across the lawn of the paternal home

small flowers flourished

as if Marta-Liisa’s joy

had suddenly spread, filled

the whole house.

The only living branch of the old cherry tree blooms,

a gathering of sap in the branch

that lets the tree forget its rotten

trunk.

The head, the old stump — the traitor —

slowly sinks into green,

justly drowning in the sea of dandelions.

EXITING SUMMER

so you feared to call a fir tree green?

to call a spring chestnut a cathedral of chandeliers?

you feared being taken for a fir needle?

for a horse chestnut?

don’t worry. it already is. you already are.

(don’t fear impossible love — even

the celts knew it — and besides

it’s the only kind)

A WANDERING RAINBOW

Well, yes, having boarded the bus we could

at least put our elbows on the armrests

and settling into both seats

keep to ourselves.

Fine, your moss-colored eyes in any case

will forgive. You will take back with you

only the rainbow crossing the gray

glass sky, from red sunglow

at one edge to the full moon’s sheer face

at the other, the green cemetery of Viljandi,

after rain — even before that

a big red cow against real grass,

with background clouds, about which

you rightly asked whether they have

such fine conformation only here,

only seen by such exotic eyes

as yours, from such a distance?

TRAINS

1.

To the train! To the train!, a cherished

colleague called. Everyone is

aboard already: diligent compatriots,

ministers, poets,

the beauty of humankind

on the Paris-New York Express!

Bon voyage, then. Once my Latvian

great-grandmother, who never in her life

got angry, told my mother,

who sat in her lap

amid the world war’s smoking ruins,

when the morning whistle from the station

pierced Mõisaküla’s bone and flesh:

That horse never waits.

2.

This train was different. Crawling

slowly, sniffing the grass,

making long stops only

in border towns. It made strange

feints into clouds, grubbed up

graveyard dirt, dragged

the seafloor lazily amid fish,

picked up from stations

latecomers, lovers,

fiery-eyed young men

from the platforms, you who

had forgotten how happy you were

yesterday at the kitchen

table, humming along

with abba, your fingers

drumming on your knees,

eyes seaweed,

teeth young reed.

56

On the second day of Christmas in Tartu

it started to snow.

The soul was relieved.

The old woman Rose who by a miracle

escaped from Auschwitz

and loved life’s colors infinitely

but became blind, writes from

Fort Washington Street that even in darkness

she sees what is light and what

shadow. And thanks God.

The whole earth and everything on it

is wrapped in light.

Snow and soul.

Soul and snow.

57

She sleeps she sleeps she sleeps.

No longer will she know me.

She sleeps, my dear mother.

Her voice reaches only sleep.

She sleeps.

Arms still rise toward gray snow.

Eyes beat the walls of sleep.

Come to the shelter, dear mother, come,

come from the night to my memory’s snow.

8 November 2007

60

Outside snow melts It soaks

into you Mother but you open

the door and peek in — old,

young, without crutches!

You didn’t go to school today?

Snow falls into you Are you

not afraid of cold Mother?

63

It was something about

dogs. Why

did you weep, was the movie sad?

— Not really sad, just

soulful. Then you feel it

rightly. Look, at last

snow has arrived. Wipe

your eyes, dry them,

the new year starts now.